As friends will know I started writing a memoir in January 2018, having reached the last of the three goals I had set myself in 2013. Taking my youngest daughter to secondary school ( Eloise would not let me walk with her; parents don’t walk with their children to secondary school). It was September 2017, four years and a month since been given the terminal diagnosis. The average life expectancy with my metastases was twenty two months and I had read in the medical literature, no one had lived more than four years. I had become an outlier in medical science, my case was not typical or perhaps not typical because I stopped medical treatment and tried something different. Either way my memoir is my experience with the cancer that was first diagnosed on April Fools day 2011, that I got the all clear for in August 2012 and was then told in August 2013 that cancer had returned and now had spread (presumably it never left but was not visible on scans).

Below is the first chapter of my Cancer memoir, the worst period of my journey. The consultant had removed all hope, The cancer was now incurable and I was going to die in the near future. According to the government, it is illegal for anyone else to offer cancer treatment, because the medical establishment believe if the biomedical model and their scientists cant help, no one can and anyone offering alternatives are just peddling false hope. However these laws cant stop me treating myself in an alternative way and trying different things. Its in my notes at the Royal Marsden that I took Cannabis oil to treat my cancer having stopped chemotherapy, I often joke I would need to live to 150 before doctors at the Royal Marsden would say its amazing Richard is still alive. In the preceding years I have had consultations with different consultants not one has shown any interest in what I did. An unscientific protocol as recommended by a Canadian guy called Rick Simpson in 2014. Make no mistake as more information comes out of the therapeutic benefits of cannabis, it was Simpson more than anyone, who is the pioneer of using cannabis oil therapeutically in fact he has served jail time for his efforts. When I took it there was very little on the internet about cannabis oil, only his website. Even though in 2001 GW pharmaceuticals were granted a licence to grow cannabis and make a product called Sativex which appeared to help Multiple Sclerosis (MS), It was all very hush hush and the word cannabis was not used when discussing Sativex before 2013.

In August 2018 I was on Good Morning Britain talking about Children’s Health and whether UK children needed all these vaccines that they were been given. Doctor Hillary Jones presented the medical view. Have written my Masters in dissertation on the DTaP vaccine in 2004, something they were unaware of and no doubt surprised at my level of knowledge on the subject; the shows presenter Kate Garraway sneered at me; “Why do you think you know more than the Doctor”. Not wishing to be confrontational on live TV, or quote my Masters standard of education, I recounted my cancer story, which usually blows people away and my way of saying, doctors don’t know everything. She may not have have believed me, but she was clearly not impressed. Most TV presenters and journalists are now just spokespeople doing PR for the corporations that advertise on their media platforms.. If you go into a butchers shop, the butcher is probably aware that its good to eat fish and vegetables as well, but is he going to talk to the customer about it probably not. With her question in mind I have dedicated my memoir to Kate Garraway and Journalists who don’t have the curiosity to question corporate power.

When I was first diagnosed, they said I was stage 2 and survival rates were 80%, after surgery they found it had spread to Lymph nodes (stage 3) which meant Survival was 50% then in August 2013 survival was 0%, This is the day I start the memoir with, then I return to how it all began in 2010. I explore the sdmoke and mirrors of public relations masquerading as science using statistics and percentages to mislead the public to think science is some kind of “truth” rather than a method of investigating the assumptions people make about health and wellbeing. In April 2016 I became a cancer survivor, researchers could now tick the original box of 80% survival and enter it as part of cancer science. However that ticked box tells you nothing about my cancer story and no doubt thousands perhaps millions of others. My “anecdote” is dismissed, I was an outlier who tried something different and would be excluded from a research study as a “confounder” as I did not complete my course of chemotherapy.

I have had so much radio therapy and chemo and CT scans I am bound to get cancer again one day, no doubt the sceptics will be dancing on my grave the way they do on others who choose to try something different. I waited to write about my experience until I had gone way way beyond the medical predictions, and show that a cancer diagnoses does not necessarily mean the end, in my case it was the start of the most exciting interesting period of my life.

IF

If you can keep your head when all about you;

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too.

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster,

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make a heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

by Rudyard Kipling

Chapter 1

(Cancer drove me up the wall}

Beginning of the end or the end of the beginning?

The sound of rush hour traffic had finished and the last patient of the day was waiting when Julie, my receptionist, asked if she could go home early. I looked at the young woman sitting there, waiting for a chiropractic ‘doctor’ to see her, and thought that being alone with me in the clinic for thirty minutes might not be what she had planned for her day. I asked Julie to stay, as this woman looked young and might not have had the life experience to enjoy my childish sense of humour.

A Danish newspaper once described my successful coaching methods for the Hellerup Idraets Klub (HIK) women’s football team, as a combination of Irish charm, flirting and shouting. Those who know me today would confirm that little has changed since: I am going on to seventy and still feel and behave like a teenager.

You are expected to be ‘professional’ as a health care practitioner and not scare your patients away. Wearing a suit and tie and being rather dull is the easy option, but I prefer to introduce an element of humour to my work. Some people may not like this approach, which is fine; after all, you can’t please everyone all the time.

After the initial pleasantries, we sat down so I could take the patient’s medical history. ‘Are you taking any medications?’ I asked. ‘Antidepressants’, she casually replied. I barely concealed an eye roll as I jumped to an ill-informed conclusion as to why this 21-year-old was on antidepressants. A row with the boyfriend, perhaps? Or did Daddy not buy her the latest iPhone?

‘What have you got to be depressed about?’ I arrogantly asked my patient. ‘What I would give to be 20 again with my whole life ahead of me. In 2011, I was diagnosed with cancer and treated with radiotherapy, surgery, and chemo. I thought I would die many times, but never considered medicating away the mental anguish I was experiencing.’

Her eyes welled up: ‘My little brother died of a brain tumour last month and his twin brother is being treated for the same cancer. The radiotherapy has caused brain damage.’

It was as if I had been hit by a train and bits of me were scattered all over the track; where could I start to repair the damage? Not for the first time, had I spoken without engaging my brain. I was standing in a massive hole with no way out except to apologise for my appalling assumptions. I thought of the day at the Royal Marsden when they asked me to allow a child to go before me while waiting for my radiotherapy. At that moment, I realised having cancer is not the worst thing that could have happened to me; one of my children having it would be unimaginably worse.

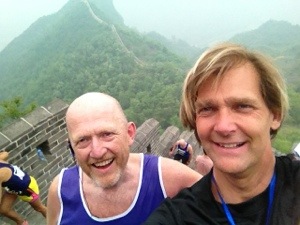

I treated my patient. She may never know how grateful I am to her for bringing me back to earth from the high I had been on since completing the marathon on the Great Wall of China three months prior.

I believed my torrid affair with cancer had ended twelve months earlier when I was given the ‘all clear’ during the London Olympics. I even completed a marathon on the Great Wall to show everyone how recovered I was. I had beaten cancer; I felt indestructible. An ego like mine loved hearing how courageous and inspiring I was. Then I met this young woman and realised that she was the courageous one. She just needed a little help to face this massive ordeal in her life. She could have run away from her brother’s illness and let her parents deal with it. But courage is when you’re given the option to run away from responsibility, yet you choose the difficult option of staying. Particularly when your choice is made for the benefit of others. However cancer patients don’t have a choice. It does not matter whether we have courage or not, we just have to get on with life as best we can.

The following morning was my penultimate day at work before the family and I were heading for our summer holiday in Italy. There were just a few loose ends to tie up. Janette, my partner, was focused on finishing the annual tax returns for my chiropractic practice, ‘Spinal Joint’, finished before we left. And me? I was thinking about my tennis match that afternoon; victory would put me top of the league table.

Before the match, I had the small matter of receiving my scan results from my first annual check-up at the Royal Marsden. I had planned to ask my consultant to sign the ‘Great Wall’ t-shirt, I was presented with after completing the marathon which I then hoped to make my profile picture on Facebook.

However I did not recognise this consultant, however. ‘Where is Sheela?’ I asked. Sheela Rao had become my main oncologist through treatment at the Royal Marsden. She had a sense of humour and it helped when I could joke around with her during visits.

‘Sheela is on annual leave’, the consultant responded with an uninspiring expression on her face, like someone tasting Marmite for the first time.

‘I told the scan people I was happy to have this appointment when I got back from my holiday.’

‘We thought it was better you came in before. So how are you feeling, Mr Lanigan?’ she asked in a tone that indicated she was not expecting a positive answer.

This was the moment I should’ve realised all was not well, but I had been thinking about my response to this question for months since my annual check-up had been arranged. I was given a platform and I wanted to pay homage to my ego. My face beamed with a smile.

‘Fantastic!’ I responded. ‘I have not felt this good since my 20s. I ran ten miles yesterday in my best time ever!’ I then proceeded to tell her about the marathon in China.

I like to think I am a good storyteller who makes people laugh at the right moments, but not once did she crack a smile. ‘What a miserable cow’, I remember thinking. I had just completed one of the hardest marathons in the world, 12 months after major surgery and 12 cycles of chemotherapy, and she did not seem remotely interested. So I stopped talking.

After a pause, she announced that she had some bad news.

The first thing that came into my head was that she was going to tell me my car had been clamped. Parking is always a problem in hospitals and I had found this spot behind the bikes in the Marsden. While it could technically fit my small car, it was not a designated parking space.

‘The results of your scan are not good’, she clarified.

She waited for me to say something, but I was too preoccupied with trying to remain calm. Every time I had gone to get results from a consultant previously, I had brought my friend Rich Parkin to take notes, as this allowed me to concentrate on the questions I wanted to ask and remain relaxed while he focused on the answers. You want someone calm beside you when it feels like your world is collapsing. Complex health information is difficult to assimilate, especially when it’s not what you are hoping to hear. You only have 15 minutes with a consultant, so it’s important to have all your questions written down and someone else on hand to write down the answers.

I was here to boast about my marathon, not to ask questions about her ‘bad news’. I could not think of a single question to ask. After another pause, which seemed to last an eternity, she continued. ‘Your cancer has returned, spread, and is incurable.’ My mouth was open but my brain was unable to formulate words.

Having qualified as a chiropractor in the 90s, I had been trained to read x-rays and MRI scans. When my rectal tumour first appeared on the screen during a colonoscopy in 2011, I was seeing the scan that would tell the ‘experts’ how serious the cancer was and whether the tumour had metastasised to my liver or found a hiding place in another part of my anatomy. Cancer is not a binary disease; the difference between stage 1 and stage 4 is perhaps similar to the difference between having a wart on a finger and gangrene in the arm. Worth remembering next time we hear a celebrity milking their ‘cancer scare’ story to the media.

‘Has it spread to my liver?’ I said with an air of confidence, trying to show the consultant that I wanted details and knew my stuff.

‘No’, she replied.

Shit! Cancer spreading to my brain had always been a huge fear.

‘Is it in my brain?’

‘No, it’s not in your brain, It’s in the lymph nodes around the aorta.’

‘Only lymph nodes!’ I thought with relief. If it was only a few nodes, they could be surgically removed; serious, though not necessarily terminal. Unfortunately, surgery in this area is too dangerous to perform. For this reason, surgeons frequently call this anatomical region ‘Tiger land’.

‘How many lymph nodes are affected?’ I asked.

‘They are not tennis balls’, she said in an exasperated tone and handed me the CT report, essentially implying that my questions would be better answered by reading the report myself. Every organ I would have considered at risk was listed as ‘clear’, but the final paragraph of the report began with the word ‘unfortunately’. My heart thumped heavily. I felt this knot tightening in my stomach. Cancer cells had metastasised distally to the lymph nodes; they were one and a half centimetres in diameter, spreading to other organs, and would eventually kill me. This consultant was telling me there was no hope.

It reminded me of that moment at the start of The Hunger Games when Katniss and Peeta eagerly sought survival advice from Hamish. He looked at them with pity and said, ‘Embrace the probability of your imminent death and know in your heart that there’s nothing I can do to save you.’

My cancer had spread to lymph nodes I didn’t even know existed. They surrounded the aorta and measured 15 mm in size. I must have stayed in bed the morning we had that anatomy lecture on lymphatic drainage of the pelvis at university.

I did not understand how this could be incurable. Lymph node spread is stage three, not stage four. My primary tumour was found in my rectum in April 2011 and had spread to only one lymph node. I was told I was lucky it had been caught early. The tumour and a few lymph nodes were removed and I received 12 cycles of chemo to prevent cells from spreading distally. And now this medical version of Hamish was telling me the average life expectancy was only 22 months, and I had to have more chemotherapy?

To be fair, the Registrar looked young and unseasoned, and I suspected that she had limited experience playing the ‘grim reaper’ to her patients. And who was I to critique a clinician’s bedside manner after my performance with my young patient the previous evening?

I can’t remember much more about the meeting. I was in shock as I left. How could I have been terminally ill while running that marathon? Then I thought of my patient who in a strange way had prepared me for this awful news and brought my feet back to earth. I once again began thinking how lucky I was that it was me and not one of my girls.

As I got out onto the road, I started noticing things that I had always taken for granted: the trees, the different sounds of the traffic. The phone rang; it was Janette.

‘How did it go?’

‘Not very good. The cancer is back and they say it is incurable. They have given me 22 months.’

‘That’s not funny’, she said in an exasperated tone. ‘How did it go?’

I started laughing. ‘It’s true! Twenty-two months is all you have to put up with me for.’

‘Stop it, you’re not funny’, she said. ‘What happened?’

‘I told you’, I laughed harder, thinking back to the reactions I got when I announced I had cancer on the first of April 2011, not realising that it was April Fool’s Day.

‘Stop it now.’

This continued until she asked me to swear on the girls’ lives. I did, and there was a pause at the end of the line.

‘What are you going to say to them?’ she asked, her voice quivering. They were waiting for me at their grandparents’ house.

‘I will wait until you are home and then pick them up after my tennis match’, I responded flatly.

‘You’re still going to play tennis?’ she asked incredulously.

Most of the useful things I have learned about dealing with people and adversity in life ARE from boarding school and competitive team sports. You don’t always get what you deserve in life, but good friends help you through the difficult times. In sports, teammates look after each other, and if the team is successful, positive emotions and memories bond you to each other for life.

Individual sports are different: you are on your own, there are no hiding spots. Sports like tennis require great mental strength to succeed at, and many of the battles fought are with a player’s own self-belief and ability to cope under pressure. Sports commentators speak of a ‘pressure’: a putt to win the Ryder Cup, a penalty shot in the World Cup Final, a serve to win Wimbledon. All situations where the athlete is on their own. Now I was facing the ultimate pressure: death.

My son, Frederik, spent his formative years in Denmark and then Norway. He was a big tennis talent who became the youngest men’s national tennis champion in Norway at age sixteen. He could have been a top 100 tennis player, but was too young when he went on the circuit and did not have the type of insular mentality required for an unforgiving sport like tennis. Mentally, Frederik is a social person more suited to team sport. At age 25, he quit the tennis circuit to play semi-professional football for Braatvag in Norway. When he retired from football, he moved back to Denmark, began playing tennis again for fun and won a national team tennis title with Lyngby in 2021.

The ability to deal with pressure is key to success in sport, business, and life in general. Imagine, if you will, being asked to walk along a narrow length of wood. Placed on the ground, the challenge is laughably easy. Placed 20 feet up in the air with the added prospect of falling, it becomes unimaginably difficult.

I have always considered mental strength to be very important and this news gave me the opportunity to show Frederik what it truly meant. I was going to play my tennis match as planned and I was going to win. I would only think about the cancer prognosis afterwards.

I phoned Frederik to tell him what the consultant had said and could immediately hear the emotion in his voice. The grim reaper had visited Frederik’s house the previous year and taken both his 17-year-old sister Thea and his stepfather within weeks of each other. His strength for me that day showed me that his mental fortitude was much stronger than I had ever given him credit for.

When I began telling others about my diagnosis in 2011, reactions varied. Some people would get very upset. Frederik knew how uncomfortable crying made me. What can you do? I might have thought they were silly getting so upset, but I would not want to tell another person how they should feel about something. I would never feel sorry for myself and the last thing I would ever want from someone else is pity. Shit happens, people die, life goes on, and everyone does the best they can and I had a tennis match to play.

The sun was out when I arrived at the tennis club. Probably for the first time, I observed the normality of people coming and going in a sports club. I thought how nice it would be, if the world were to stop turning, to give me time to absorb the traumatic news I had just received. Of course life is not like that and I am not the only person with problems to deal with.

I won the toss and proceeded to serve. My opponent had not won a single match in the league, and as soon as we started hitting I could see why. After winning the first game to fifteen (he got lucky on a mishit return), we changed sides. I walked to the other side like a peacock flaunting his beautiful feathers. I was probably 20 years older than this guy and was going to show him no mercy. I got into the ready position to receive his serve.

He wound up and hit his first serve limply into the net. As I waited for the second in the hot sun, I was consumed with an overwhelming feeling of coldness; a chill so complete that made the hair stand up on the back of my neck. I could see goose bumps on my arms and became aware of a voice in my head, saying, ‘You are going to die, you are not not going to see your girls grow up.’ I didn’t even notice where the second serve landed. My opponent moved to the other side of the court for his next serve, looking pleased with himself as he shouted, ‘Fifteen-love’.

His next serve was set up to be drilled down the line, but my legs and arms had turned to jelly, so my return was out. ‘Thirty-love’, he shouted. I wanted to show Frederik how strong I was, but I had nothing. There on the court, I believed I had started to die. My future was disintegrating before my eyes and there was nothing anybody could do to help me. I lost the set 6-1.

At the changeover, my opponent was feeling really pleased with himself and asked me about the other opponents I had beaten in our league. I couldn’t take anymore of this slow torture. ‘I can’t play any more’, I said. ‘I have to go’.

‘Why?’ he asked. He was no doubt expecting some sort of meagre excuse.

‘I have just been told that I only have a few months left to live and I don’t want to waste any more of my time on this.’

The look on his face was priceless. I was half-tempted to describe my cancer, the confirmed tragedy of my future, in excruciating detail. My response was ruining his first and only tennis peak. It’s a strange feeling having one side of your brain in such turmoil and the other side wanting to take the piss out of a complete stranger. But not even this could distract me from the truth: I had cracked and I knew it. The purpose of me being there was to show Frederik how strong I was and I had failed. I had reached breaking point and just wanted to return home to my girls.

Cancer was now in control of me and I was falling apart. The tennis match was a perfect analogy for what was about to happen to my life, and my kids were going to bear witness to it. I sobbed as I drove to pick up the girls, wallowing in my own self-pity. If I couldn’t even beat that guy, I was no match for cancer. As McGreggor would say in Dad’s Army, I was “doomed”. I felt pathetic, but like so many times before, it was my young children who helped me get a grip.

After the tennis I drove to Janette’s parents’ house. They did not say much, I could see they knew from the sadness in their eyes. We were just out of their driveway and Isabelle asked what the doctors had said. I had never hidden anything from the kids – death is an inevitable part of life and it is daft to think you can protect anyone from it, including your own children. It was just unfortunate they were so young. But, in my opinion, the longer the children had to get used to the idea, the easier it would be when the time came.

‘We will talk about it when Mammy comes home, I replied.

Like a dog with a bone, Isabelle wouldn’t let go and repeated the question. I fobbed her off again.

‘The cancer is back, isn’t it?’

‘Wait until Mammy gets home. We will talk about it then.’

She repeated, ‘The cancer is back, isn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Are you going to die?’

‘Yes.’

Not much was said for the rest of the journey. Cancer is something that never leaves you, even after getting the all clear and believing you are cured, aches and pains create sinister thoughts, and tension headaches become ‘brain tumours’.

After we got home, Molly disappeared. I knew that she was in her room crying, but there wasn’t a lot I could say until Janette got home from work. When children are upset, you are supposed to tell them that it’s going to be alright. But I could not lie; it was not going to be alright. I was going to die and they would have to cope without me and that’s why I left her to it until she was ready to come down and talk.

I considered the facts that there must be advantages to knowing in advance and that 22 months was only an average. There must be some hope. I looked up metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes on PubMed, but quickly realised that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. According to the medical literature in 2013, no one in my situation had survived more than 4 years. I was well and truly fucked. I clung on to my last hope: that my usual consultant, Sheela Rao, would be back the following week and would call me. Perhaps they had mixed up my scan with someone else’s and she would tell me it was all a mistake.

At that point, I had documented every stage of my cancer experience on Facebook, but now had neither the will nor desire to share my news on social media. I had given many people hope that cancer could be beaten. I was contacted by cancer patients all the time, and while I did not want to get too involved in others’ journeys, it felt good to give them hope when doctors told them there was none. I had put myself up on a pedestal and it was not going to be pleasant falling off of it. I was not a unique fearless individual, after all, but would die a horrible death like everybody else. I decided not to say anything and only tell my closest friends.

I first called John Costelloe, whom I had known since age eleven. In 1969, we shared a dormitory in boarding school. In addition to being one of Europe’s leading environmental scientists, John was a minefield of information about cancer, having had radical neck dissection ten years earlier to combat stage 3 throat cancer. John’s experience had taught me that cancer treatment was as much about luck as the competence of the consultant in charge of your care.

John was the toughest man I had ever encountered on a football or hurling field. He won All-Ireland medals at school and university, as well as an inter-county minor for Kilkenny. For five years, we trained together at school, but I never came out on top of a challenge with him; he was far too quick and strong. Sometimes, John would let me get to the ball first in training, so he could batter me and make everyone laugh, as I was not blessed with the speed to get away.

John often dared me to tackle him and, in the manner of Robert the Bruce, I was always up for the challenge. He knew he was making me a better player by building character and determination. I described John as a ‘Neanderthal man’, and at university, he even grew a big bushy beard to look the part. In 1980, however, John chose to focus on his science career over sports. I couldn’t believe it; I wanted so much to have his athletic ability but he was voluntarily giving it up. Years ahead of his time, he was instead committing to saving the planet’s oceans and rivers.

The neck surgery John had for his cancer in 2005 had condemned him to a life of constant shoulder and neck pain. Radiotherapy had additionally destroyed his saliva glands and left him with persistent dry mouth. But he survived, and as a survivor, the news that it had come back in a friend was a major blow and a reminder of his continued vulnerability to the ‘Emperor of all Maladies’, cancer.

John was silent on the line after hearing my news. I broke the tension with a joke. ‘I am finally going to beat you in a race’, I said, and we laughed. Little did we know the race was not over, and as we spoke, an aggressive tumour was growing in John’s brain which would be discovered within the next few months.

From there, I called Richard Parkin. He was his usual stoic self. Ever since I was first diagnosed, he had been the one by my side when I received my scan results. But this time, I did not think I needed someone there to take notes. I am not usually superstitious, but I was kicking myself for not bringing him to the meeting with the consultant.

Rob Trew, a chiropractic colleague, made me laugh when we spoke. He told me how he had lunch with a friend that afternoon who had just been diagnosed with cancer. He had shared my ‘inspirational’ story and now he would have to call his friend back and say, ‘Forget it, it’s a mistake, Richard is going to die after all.’

When you hear devastating news, you wonder how you will ever laugh again, but it’s surprising how quickly humans can adapt to heartbreak when they have good people around them. I Skyped my sister Eleanor who gave me the standard, ‘Fuck off with your dying shit’, followed by our usual banter. She is two years younger than me, so my mother was always begging me to be nice to her. But that was never going to happen. Eleanor was the blotting paper for my black humour and I tormented her and her friends.

After our conversation ended, she incorrectly assumed she had disconnected and began to weep. I was deeply moved by the sight, but started laughing and taking the piss immediately; you would have to understand the relationship I have with Eleanor to appreciate my reaction. Upon hearing my voice, Eleanor pulled herself together and laughed along with me. The more I took the piss, the more we laughed. I said, ‘Mammy said you hated me’, which only prompted more laughter.

I then called Klaus in Copenhagen, another close friend from my time in Denmark, who had gone to China with me for the marathon. He recalled his reaction to hearing the news the first time, when I went public with my cancer diagnosis on April Fool’s Day. We laughed about it, which was important for me, as I had set out to live well with cancer. I would not be a victim, but would live my life normally with friends who did not pity me as a victim of this horrible disease.

Then I called Ole Wessung, a Danish entrepreneur, chiropractor and motivational speaker. In the late 80s, Ole came up with the idea of bike sharing which is now commonplace in all major cities across Europe. He spent thousands designing the prototype bike (‘By Cyklen’), which I dismissed as the stupidest idea ever. ‘Everyone in Copenhagen owns a bike’, I said.

Ole had also accompanied me to China to run the marathon. He routinely did Ironman triathlons and promised friends he would carry me to the finish line if needed. He tried to be upbeat by regurgitating a bunch of slogans he used at his motivational seminars. But in an intimate setting such as this, they fell flat and he knew it. Finally, he said, ‘Do you remember what you said to me at the end of the marathon?’

‘No!’

‘You said this was the hardest thing you had ever done in your life.’

‘Yes, it was.’

‘No it won’t be’, said Ole. ‘That was just the training for what you are about to do now. You are such a show-off that beating stage 3 cancer was never going to be enough for you. You had to wait until the doctors said there was no hope just so you could prove them wrong.’

I guess it had a nice ring for those attending Ole’s motivational seminars, but I had to wonder if things like that really happened in real life. While it brought a smile to my face, in reality, I knew I was fucked. But then again, no one gave Muhammad Ali a chance against George Foreman in ‘74, Arsenal in their last match against Liverpool in ‘89, Denmark in the ‘92 Euros, or the NBAs Cavaliers against the Warriors in 2016. My seven-year-old daughter only picked the winning horse in the Grand National at 100 to 1 odds because she liked the jockey’s colours. It was a reminder to always keep hope alive, because without it, you might as well be dead.

Janette and I stayed up talking until the early hours trying to formulate a plan. I’d had an amazing life and had done almost everything I had ever wanted to do so I would not be making a ‘bucket list’. Two years of living after a cancer diagnosis had made me appreciate the simple things in life like spending quality time with people I loved. Some say you don’t appreciate life until you have faced death. I wanted to create good memories for the kids and therefore set three goals for myself to achieve:

September, 2015: 25 months away, to see my twin daughters Molly and Isabelle off to secondary school;

March 21st, 2017: 40 months away, to ring in my 60th Birthday; and

September, 2017: 49 months away, to see my youngest daughter off to secondary school.

Achieving all three would mean that my outcome had veered well into miracle territory, as no one had yet lived that long, but I optimistically planned to beat the record by one month. And if I was still alive in 2018, I vowed to write a book.

I motivated myself by thinking of journalist Hugh Mcllvanney’s words after one of the most iconic moments in sport, when the ageing Muhammad Ali took the World Heavyweight title back from the mighty George Foreman in Zaire in 1974. The ‘experts’ said Ali had ‘no hope’ against Foreman and Mcilvanney compared Ali’s return to greatness with the ‘resurrection’ of Jesus Christ. ‘Muhammad Ali would not settle for any ordinary resurrection, not only did Ali roll away the rock in Zaire, he hit George Foreman on the head with it.’

As Ole had said, the China marathon was only me ‘rolling the rock back’. I had to add an additional flourish and show it was possible to live well with terminal cancer and survive, despite what the experts were predicting.

Well-written blog! Have you ever curious about how a soundboard actually functions? If so, It’s a device digital or physical that plays preset sound effect with just one button tap. Check out the post to learn more!

I enjoy, result in I discovered exactly what I used to be looking

for. You’ve ended my four day lengthy hunt! God

Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

I have been browsing on-line more than three hours these days, yet I never found any fascinating article like

yours. It is lovely value enough for me. In my view, if all website owners and bloggers made just right content as you did,

the net will likely be much more useful than ever before.

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I

could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience

with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything.

I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

Saved as a favorite, I like your blog!

Hi there, You’ve done an excellent job. I’ll definitely digg it and individually recommend to my friends. I’m confident they’ll be benefited from this site.

In fact no matter if someone doesn’t know afterward its up

to other people that they will assist, so here

it takes place.

I all the time emailed this webpage post page to all my friends, for the reason that if like to read it then my links will

too.

В казино Up X вам предлагают невероятный игровой сервис. Мы предлагаем широкий ассортимент азартных игр, включая слоты, рулетку, покер и блэкджек. И это еще не все! Наша программа лояльности включает турниры и акции, которые делают игру еще интереснее и выгоднее. Как показывает практика, участие в акциях и турнирах значительно повышает шансы на выигрыш. Когда лучше всего начать играть? Ответ прост: лучший момент — это сейчас! https://russkij-tekst.ru/. Какие шаги предпринять перед игрой? Перед началом игры ознакомьтесь с нашими правилами и условиями для комфортного старта. Используйте специальные условия для постоянных игроков, чтобы максимизировать свои успехи. Если вы давно не играли, начните с демо-игр, чтобы вспомнить правила и почувствовать азарт.

I like what you guys are up also. Such intelligent work and reporting! Carry on the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my website 🙂

Appreciate the recommendation. Will try it out.

Howdy, I believe your web site may be having web browser compatibility problems.

When I look at your blog in Safari, it looks

fine but when opening in IE, it’s got some overlapping issues.

I merely wanted to give you a quick heads up! Besides that, wonderful website!

Вас приветствует Stake Casino — место, где вас ждут лучшие игры, эксклюзивные бонусы и потенциал для крупных выигрышей. https://stake-xpboost.wiki/.

Что отличает Stake Casino?

Интуитивно понятный интерфейс для игроков всех уровней.

Уникальные игры от ведущих провайдеров.

Выгодные акции для новичков и постоянных игроков.

Доступность на всех устройствах — играйте где угодно!

Не откладывайте, начните играть в Stake Casino и выигрывать прямо сейчас!

Your means of describing the whole thing in this piece of writing

is really fastidious, all be able to effortlessly

understand it, Thanks a lot.

For a truly secure and reliable betting experience, trust is everything. That’s why I always choose verified platforms from안전토토사이트 추천

For a truly secure and reliable betting experience, trust is everything. That’s why I always choose verified platforms from안전토토사이트 추천

Hello just wanted to give you a quick heads up.

The words in your content seem to be running off the screen in Safari.

I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with

web browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know.

The layout look great though! Hope you get the problem

fixed soon. Thanks

Dragon Money Casino is the place where high stakes and extraordinary opportunities await every player. We provide you with a chance to test your luck and win big prizes. At Dragon Money Casino, you’ll find a vast selection of games, including the most popular games for players of all levels.

Our tournaments exclusive events, where you can increase your chances of a big win. Bonus programs help boost your luck. Participate in our promotions to test your luck – https://dragonmoney-primecasino.makeup/.

When is the best time to play? Anytime you feel lucky!

Why choose us:

Quick and simple registration lets you start enjoying the game right away.

We offer personalized offers for our loyal clients, so you can get more benefits.

Play from any device, so you can enjoy the game anytime.

Добро пожаловать в Play Fortuna Casino — место, где каждый игрок может ощутить все преимущества азартных игр. В Play Fortuna Casino вас ждут самые лучшие игры с шансами на крупные выигрыши и невероятные бонусы. Здесь каждый момент — шанс стать победителем, а отличные предложения помогут вам увеличить свои шансы на успех.

Почему стоит выбрать Play Fortuna Casino? В Play Fortuna Casino мы ценим каждого игрока и гарантируем, что каждый сможет испытать удачу с самыми выгодными условиями. Наша цель — создать комфортную и безопасную среду для игры.

Когда лучше начать играть? Зарегистрируйтесь и получите доступ к уникальным бонусам и акциям, которые ждут вас в Play Fortuna Casino. Вот что вас ждет:

Мы регулярно обновляем ассортимент игр, чтобы вам всегда было интересно играть.

Бонусы и акции, которые значительно увеличат ваши шансы на выигрыш.

Простота в пополнении счета и выводе средств.

Play Fortuna Casino — это не просто игра, это шанс на настоящий успех. https://777fortuna.top/

Vavada Casino предлагает вам пространство высококлассных игровых возможностей|Vavada Casino приглашает вас, чтобы насладиться неповторимым опытом, который покорит самых искушенных игроков. В нашем казино представлены самые интересные игры в том числе рулетка, покер, блэкджек и слоты. Кроме того, игроки активно участвуют в ежедневных турнирах, что дает шанс повысить вероятность выигрыша и насладиться игрой. Участие в акциях и турнирах – это невероятно выгодная возможность снизить расходы и сделать игру еще более захватывающей. Каждая игра в Vavada Casino – это возможность быстро найти свою игру – https://vavada-battle.top/.

Когда стоит принять участие в мероприятия Vavada Casino? В любое время, когда вам удобно!

Существуют ситуации, когда стоит воспользоваться предложениями Vavada Casino, чтобы сэкономить время и усилия:

Перед тем как начать, рекомендуем прочитать нашими правилами использования.

Если вы опытный игрок, попробуйте специальные привилегии, чтобы получить максимальное удовольствие и выигрыша.

Если вы не играли долгое время, можно начать с бесплатных версий, чтобы проверить свои навыки.

Хотите испытать удачу? Тогда Hype Casino — ваш лучший выбор! Здесь вас ждут лучшие слоты, рулетка, покер и блэкджек, а также уникальная бонусная система для постоянных игроков. https://hype-playcraze.wiki/.

Какие преимущества у Hype Casino?

Удобные депозиты и быстрые выплаты с максимальной прозрачностью.

Большой выбор игр, включая последние новинки.

Специальные предложения, улучшающие ваш игровой опыт.

Регистрируйтесь в Hype Casino и наслаждайтесь игрой без ограничений!

Криптобосс Казино рады видеть вас, чтобы испытать особой атмосферой игр. Наше казино включает в себя богатый ассортимент игр, включая рулетка, покер, блэкджек и популярные слоты. А ещё, мы регулярно проводим специальные мероприятия, которые позволяют участникам улучшить свои шансы на успех и насладиться каждым моментом.

Участие в турнирах и акциях Криптобосс Казино – это идеальный вариант для любителей разумного подхода. Любой турнир в нашем зале – это возможность окунуться в азарт, обеспечивая отличное настроение – https://cryptoboss-casinotrail.makeup/.

Когда лучше всего начать играть? В любое время, когда вам захочется!

Что делает наше казино особенным:

Прежде чем начать, советуем изучить основными принципами игры.

Если вы опытный игрок, не упустите возможность воспользоваться нашу уникальную VIP-программу, чтобы увеличить шансы на успех.

Вернувшись после долгого перерыва, начните с бесплатных демо-версий, чтобы вспомнить все нюансы.

This piece of writing will help the internet users for

building up new website or even a blog from start to end.

Lex Casino предлагает возможность для незабываемых впечатлений. Мы собрали самые современные игры и автоматы, от классической рулетки до видеослотов. Каждый момент здесь наполнен азартом, где ваши мечты о выигрыше становятся реальностью. Постоянные игроки всегда ценят специальных предложений, которые позволяют наслаждаться каждым моментом.

Что делает Lex Casino особенным? Мы предлагаем уникальные возможности для всех. Присоединяясь к нашим мероприятиям, вы открываете дверь в мир настоящего азарта. Мы стремимся предоставить максимум комфорта и удовольствия.

Есть масса поводов, чтобы начать играть у нас прямо сейчас:

Перед игрой ознакомьтесь с нашими условиями – это важно для вашего успеха.

Мы предлагаем особые привилегии для опытных игроков, чтобы сделать их пребывание у нас незабываемым.

Для новичков доступны демо-версии игр, чтобы вы могли попробовать свои силы без риска.

Присоединяйтесь к нам и наслаждайтесь каждой минутой игры! https://xn--77-llceni.xn--p1ai/

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my

iPad and tested to see if it can survive a twenty five foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is

now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off

topic but I had to share it with someone!

В Нью Ретро Казино вы найдете уникальное сочетание старинных и современных игровых автоматов. Нью Ретро Казино предлагает вам незабываемый опыт с лучшими слотами, настольными играми и видеопокером. Мы создаем атмосферу, которая перенесет вас в мир азартных игр прошлых лет с современным удобством.

Независимо от вашего опыта, у нас всегда есть что-то новое и интересное для каждого игрока. Регулярные бонусы и акции помогут вам увеличить ваши шансы на победу и сделать процесс игры еще более захватывающим. Присоединяйтесь к Нью Ретро Казино и играйте в любое время и в любом месте

Легкость регистрации и простота интерфейса.

Промоакции, которые делают игру еще более выгодной.

Удобные способы пополнения счета и вывода средств.

Играть в Нью Ретро Казино можно как на компьютере, так и на мобильных устройствах, где бы вы ни находились.

Присоединяйтесь к Нью Ретро Казино и наслаждайтесь выигрышами уже сегодня! https://newretro-fortune.makeup/

Vavada Casino — это ваш шанс выиграть большие деньги с лучшими играми и щедрыми предложениями. Мы предлагаем все популярные слоты, а также бонусы на депозит для всех наших игроков. https://vavada-zone.buzz/.

Преимущества Vavada Casino:

Простой интерфейс для быстрого старта.

Высокие коэффициенты для всех игроков.

Мульти-валютные опции для удобства пользователей.

Регулярные турниры с большими призами.

Начните играть в Vavada Casino и испытайте удачу прямо сейчас!

Really quite a lot of helpful advice!

Вас приветствует Stake Casino — место, где вас ждут лучшие игры, щедрые акции и большие выигрыши. https://ask-22.ru/.

Что отличает Stake Casino?

Простой и удобный интерфейс для игроков всех уровней.

Индивидуальные и эксклюзивные игры от ведущих провайдеров.

Выгодные акции для новичков и постоянных игроков.

Возможность играть с мобильного — играйте где угодно!

Не откладывайте, начните играть в Stake Casino и выигрывать прямо сейчас!

Вас приветствует Stake Casino — место, где вас ждут лучшие игры, эксклюзивные бонусы и большие выигрыши. https://stake-playloot.space/.

Что отличает Stake Casino?

Простой и удобный интерфейс для игроков всех уровней.

Уникальные игры от ведущих провайдеров.

Приятные бонусы для новичков и постоянных игроков.

Доступность на всех устройствах — играйте где угодно!

Не откладывайте, начните играть в Stake Casino и выигрывать прямо сейчас!

cas5n0

I used to be suggested this website via my cousin. I’m no longer sure whether or

not this post is written by means of him as nobody else realize such unique approximately

my problem. You are amazing! Thanks!

Добро пожаловать в Azino 777 — ваш надежный проводник в мир высоких ставок и невероятных эмоций. Наше казино создано для тех, кто ценит азарт, безопасность и возможность заработать. В Azino 777 каждый игрок имеет равные возможности для крупных выигрышей.

Почему Azino 777 становится выбором номер один для игроков? Наши пользователи ценят безопасность и честность игровых процессов. Регулярные предложения и уникальные акции создают дополнительные преимущества для каждого клиента.

Когда стоит начать свой путь в Azino 777? Нет причин откладывать: регистрация займет всего пару минут, а награды начнут поступать сразу после первого депозита. Что делает нас уникальными:

Вы можете начать играть мгновенно благодаря простой и удобной навигации.

Мы сотрудничаем с топовыми разработчиками, чтобы предложить лучшие игровые продукты.

Вывод средств без задержек и дополнительных комиссий.

С Azino 777 ваш игровой опыт будет не только увлекательным, но и прибыльным. https://azino777page.com/

That is a really good tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Simple but very accurate information… Thank you for

sharing this one. A must read post!

Познайте безграничные возможности с Slotozal Casino, где времяпрепровождение превращается в праздник удачи. В нашем казино представлен огромный выбор слотов, классических развлечений, таких как рулетка, блэкджек, покер.

Что делает Slotozal Casino невероятным? Мы стремимся предложить лучшее обслуживание, чтобы каждая игра стала захватывающей. Хотите испытать удачу? У нас постоянно идут захватывающие турниры, которые открывают новые возможности для каждого игрока. Присоединяйтесь сейчас и убедитесь в этом лично – https://slotozal-funorbit.space/.

С нами каждый ваш день наполнен азартом и выгодой. Перед началом ознакомьтесь с нашими правилами, чтобы ваши ставки были комфортными:

Если вы новичок, начните с бесплатных версий игр.

Опытным игрокам доступны эксклюзивные бонусы и VIP-привилегии.

Если вы давно не играли, вернитесь в ритм с демо-режимом.

С нами вы всегда на шаг ближе к своей мечте!

Hype Casino — это место, где выигрывают! Здесь каждый найдет что-то по душе лучшие слоты, захватывающие карточные игры, а также уникальные промоакции для увеличения выигрышей. https://mart-igr.ru/.

Почему стоит играть в Hype Casino?

Высокая скорость вывода выигрышей без комиссий.

Ассортимент игр, которая постоянно обновляется.

Эксклюзивные бонусы, позволяющие играть с максимальной выгодой.

Испытайте удачу прямо сейчас и выигрывайте с комфортом!

Hi there! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone!

Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look

forward to all your posts! Carry on the great

work!

Wow, incredible weblog format! How lengthy have you

been running a blog for? you made blogging look easy.

The whole look of your site is wonderful, let alone the content material!

Ramenbet Casino приглашает вас погрузиться в высококачественные азартные игры. Мы предлагаем широкий выбор игровых автоматов, среди которых видеопокер, рулетка, блэкджек и игровые автоматы. Тем не менее, многие энтузиастов стремятся достигнуть высочайшее уровень игрового опыта. Из исследований следует, большая доля наших пользователей регулярно участвует в акциях, что дает возможность им значительно улучшить шансы на успех и насладиться игрой. Принять участие в наших акциях и турнирах — это выбор, который может сэкономить ваши ресурсы, а также предоставит возможность наслаждаться игрой. Каждая игра в нашем казино — это шанс сразу найти что-то по вкусу, не теряя драгоценного времени – https://maxfantasy.ru/ .

Когда имеет смысл участвовать в наших мероприятиях? В любое время!

Существуют обстоятельства, когда можно сэкономить время и просто воспользоваться нашими предложениями в Ramenbet Casino:

Перед тем как начать играть, ознакомьтесь с нашими условиями использования.

Если вы профессионал в играх, попробуйте нашими специальными привилегиями для максимизации вашего выигрыша.

После долгого перерыва в играх рекомендуем начать с демо-игр, чтобы обновить свои навыки.

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for betwana

As I website owner I believe the written content here is very good, appreciate it for your efforts.

Ваш путь к победам начинается с Up X Casino! Наше казино — это больше, чем просто игры, но и невероятные шансы на успех. Каждый игрок найдет здесь что-то особенное: от классических и современных игр до специальных мероприятий и бонусов. Что делает Up X Casino особенным? Наша главная цель — сделать каждую игру уникальной и незабываемой. Мы предлагаем круглосуточный доступ к играм, а также щедрые бонусы для всех. С нами выигрывать легко и приятно! С чего начать в Up X Casino? Просто сделайте шаг к успеху прямо сейчас! https://med-mz.ru/ Несколько советов для новичков: Ознакомьтесь с условиями и правилами платформы, чтобы избежать недоразумений и проблем. Используйте тренировочные версии для освоения процесса, особенно если вы только начинаете свой путь. Начните игру с подарков от казино, чтобы увеличить шансы на победу.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to

assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your blog posts.

Any way I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access

consistently fast.

R7 Казино — это место, где каждый игрок может испытать свою удачу и получить невероятные выигрыши. R7 Казино – это богатый выбор игр, которые обеспечат вам массу удовольствия и шанс на прибыль. Все наши игры созданы, чтобы вы могли не только развлекаться, но и улучшать свои шансы на удачу.

Почему вам стоит играть именно у нас? R7 Казино — это идеальное место для игры с высоким уровнем безопасности и удобством для игроков. Мы предлагаем щедрые бонусы и акции, которые помогут вам максимально повысить шансы на успех.

Когда идеально начать ваш путь к победам? Прямо сейчас! Начните играть в любое время и откройте для себя новые горизонты выигрышей и удовольствия. Вот несколько причин, почему стоит играть в R7 Казино:

Изучите наши условия, чтобы максимально эффективно использовать все возможности.

Лояльные клиенты получают эксклюзивные бонусы и предложения, доступные только им.

Если вы новичок, начните с бесплатных демо-версий и научитесь играть без риска.

R7 Казино — это ваш шанс на успех и значительные выигрыши! https://kazanring.ru/

This piece of writing is in fact a fastidious one it helps new

web viewers, who are wishing for blogging.

Hey! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting

a new project in a community in the same niche.

Your blog provided us valuable information to work on.

You have done a outstanding job!

Zooma Casino — это не просто платформа для игры, это настоящая игровая площадка, где каждый может найти щедрые предложения и уникальные игры. https://zooma-hub.buzz/.

Преимущества игры в Zooma Casino:

Множество игровых автоматов с яркими темами и высокими выплатами.

Шанс получать бонусы за участие в акциях и постоянную активность.

Надежные методы пополнения счета и вывода выигрышей, что делает процесс удобным и надежным.

Доступность мобильной версии, что позволяет играть в любом месте.

Зарегистрируйтесь и воспользуйтесь возможностями Zooma Casino прямо сейчас!

Slotozal Casino is the best choice where every player can explore the world of gambling. Our casino offers a huge selection of slots, classic entertainment, such as roulette, blackjack, poker. What makes Slotozal Casino special? Our philosophy combines innovation and comfort. Want to test your luck? We launch new tournaments daily that help improve your skills and give you a chance to win big. Don’t wait any longer and test your luck – https://slotozal-funorbit.world/. Slotozal Casino is the choice of those who value time and quality. Before diving into the gaming process, review our rules to make your bets as comfortable as possible: For beginners, we recommend trying demo versions to understand the basics. Experienced players can enjoy exclusive bonuses and VIP privileges. After a break, refresh your skills with free games. Choose Slotozal Casino – and every day will be filled with excitement and luck!

Magnificent goods from you, man. I have understand

your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely excellent.

I really like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you are

stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of

to keep it smart. I can not wait to read far more from you.

This is actually a tremendous web site.

Vovan Casino — это место, где мечты о выигрыше становятся реальностью. Наше казино предлагает лучшие игровые автоматы, а также широкий выбор развлечений, включая карточные игры и слоты. Для наших клиентов мы разработали уникальные бонусы, которые помогают увеличить шансы на победу. С нами ваша игра всегда полна ярких эмоций. Участвуйте в турнирах и получайте дополнительные награды. Наши предложения — это путь к успеху. Каждое мгновение, проведенное с нами, приближает вас к выигрышу — https://vovan-bonus.ru/. Когда лучше всего воспользоваться предложениями Vovan Casino? В любой момент, когда вам удобно. Мы выделили основные моменты, которые помогут вам наслаждаться игрой: Убедитесь, что вы понимаете правила, чтобы ваша игра была безопасной и продуктивной. Если вы опытный игрок, воспользуйтесь нашими VIP-условиями, которые сделают вашу игру еще более выгодной. Если вы впервые здесь, попробуйте бесплатные игры, чтобы освоиться и получить опыт.

obviously like your website however you need to take a look

at the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very troublesome to tell the reality however I will definitely come back again.

That is really interesting, You are a very professional blogger.

I have joined your feed and look forward to in the hunt for extra of your

fantastic post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks

Fantastic post! Are you curious about the process of converting Robux to USD? If so, I recommended a post comparing robux to usd .One must adhere to Roblox’s official exchange procedure in order to convert Robux to USD. Usually, this entails people selling goods or game passes on the platform in order to accrue Robux.For additional information, see this post.

Welcome to Money X Casino – your gateway to a new world of entertainment, where excitement meets opportunity. At Money X Casino, you’ll find an extensive collection of games, including slots, table games, and poker, all designed to provide unparalleled enjoyment. Our mission to deliver a seamless, safe, and engaging gaming environment for all our players.

Money X Casino is dedicated to offering you a first-class gaming experience, with regular promotions and bonus opportunities to keep the excitement flowing. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced player, we provide the perfect platform for you to enhance your skills and maximize your chances of winning.

Security is our top priority. Money X Casino employs state-of-the-art protection to safeguard your funds and personal details. With two-factor authentication, you can enjoy your gaming sessions with complete peace of mind.

Along with exciting games, Money X Casino offers exclusive bonuses and rewards that help you earn more while having fun. Our loyalty programs and special offers ensure that every player gets rewarded for their engagement and dedication.

Money X Casino is not just about playing games – it’s about experiencing real excitement. Join us today and discover endless possibilities in the world of online gambling!

Hi, I do believe this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I’m going to come back once again since I saved as a

favorite it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich

and continue to help other people.

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and also the rest

of the site is also very good.

Welcome to Starda Casino — пространство для по-настоящему любителей азартных игр. Здесь вас ждет невероятное количество развлечений, которые обеспечат вам неповторимый опыт. Все наши игры наполняют свежими эмоциями, будь то слоты, игры в покер, блэкджек или рулетка. Каждый турнир — это новая возможность проверить удачу.

С нами не только наслаждаться увлекательными играми, но и использовать выгодные бонусы. В нашем казино вы найдете прекрасные возможности для получения бонусов, которые помогают игрокам получить дополнительные выигрыши. Каждая акция — это возможность повысить свой доход.

Starda Casino — это все, что вам нужно для поклонников азарта. Мы готовы предложить лучшие предложения для игроков на всех уровнях. Не упустите принимать участие в акциях, которые позволяют увеличить шансы на победу. Наши турниры — это возможность для новичков и опытных игроков.

Создайте учетную запись, чтобы начать играть.

Присоединяйтесь в наших турнирах и выигрывайте бонусы.

Не упустите акции и бонусы, чтобы повысить вероятность выигрыша.

С нами вы получаете самый лучший игровой опыт, гарантированный шанс выиграть, наслаждаясь игрой — https://starda-gameripple.monster/.

Remarkable things here. I am very satisfied to look your article.

Thanks so much and I’m looking ahead to contact you.

Will you please drop me a mail?

I just like the helpful information you supply in your articles.

I will bookmark your blog and take a look at again right here

regularly. I am quite certain I will be told lots of new stuff

proper here! Good luck for the next!

Hello, for all time i used to check webpage posts here early in the dawn, because

i enjoy to gain knowledge of more and more.

Fantastic post! Interested in natural ways to boost your immune system and maintain good health? Well, check out this article. This article delves into effective natural solutions to enhance immunity. Plus, beverages like moroccan mint tea can offer additional immune-boosting benefits. Check out the blog for more details.

Vovan Casino приглашает вас испытать удачу. В нашем казино представлены новейшие игровые автоматы, а также покер, рулетка, слоты и другие развлечения. Для наших посетителей доступны интересные акции и турниры, которые помогают добиться максимального выигрыша. Каждый визит в Vovan Casino — это шанс стать победителем. Присоединяйтесь к специальным предложениям Vovan Casino, чтобы усилить азарт. Это поможет вам не только увеличить шансы на успех, но и сделать игровой процесс максимально комфортным. Каждая игра в Vovan Casino — это ваше личное приключение, которое может привести к успеху — https://gameofstocks.ru/. Когда самое подходящее время для игры в Vovan Casino? В любое время, когда вы готовы. Мы подготовили несколько советов, которые помогут вам начать максимально эффективно: Обязательно изучите правила казино, чтобы ваша игра была успешной и безопасной. Для игроков с опытом мы предлагаем специальные условия, которые помогут вам достигнуть новых высот. После длительного перерыва начните с бесплатных версий игр.

Fantastic post! Are you a gamer on the lookout for the best-unblocked games? If so, then a curated list of top unblocked game world that you can enjoy without any limitations, anytime and anywhere. These games are hosted on platforms that avoid network restrictions, ensuring safety and simplicity. Students and office workers alike love them for their casual nature. Be sure to check out the post for all the information.

each time i used to read smaller posts that as well clear their motive, and that is

also happening with this piece of writing which I am reading at this time.

At this moment I am ready to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming again to read further

news.

I really like your blog.. very nice colors & theme.

Did you make this website yourself or did you hire someone

to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to construct

my own blog and would like to find out where u got this from.

thanks a lot

This piece of writing will help the internet people for setting up new weblog or even a weblog from start to

end.

I am actually pleased to read this weblog posts which carries lots of useful information, thanks for providing these data.

Howdy, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar

one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam feedback?

If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can recommend?

I get so much lately it’s driving me mad so any assistance is very much appreciated.

Everything is very open with a really clear description of the challenges.

It was really informative. Your site is very helpful. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks for the good writeup. It in truth was a enjoyment account it.

Look complex to far introduced agreeable from you!

By the way, how can we communicate?

A fascinating discussion is worth comment. There’s no doubt that that you need to write more on this topic, it may not be a taboo matter but

typically folks don’t speak about such issues. To the next!

All the best!!

sgwlte

Good day! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group?

There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your content.

Please let me know. Many thanks

Hi! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone 3gs!

Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to

all your posts! Keep up the fantastic work!

Отличная статья! Полезная информация

для тех, кто только начал. Спасибо за рекомендации.

If you desire to obtain a great deal from this piece of

writing then you have to apply these strategies to your won blog.

Greetings! Very helpful advice on this article! It is the little changes that make the biggest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Definitely believe that which you stated.

Your favorite justification seemed to be on the internet the easiest thing to be aware

of. I say to you, I definitely get annoyed while people think about worries that they plainly do not know about.

You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defined out the whole thing without having side

effect , people could take a signal. Will likely be back to get more.

Thanks

Хотите испытать настоящее азартное волнение? Откройте для себя Play Fortuna Casino и наслаждайтесь азарт в премиальном проявлении! Тут вы найдете богатое разнообразие популярных автоматов, карт и рулеток. https://eplayfortuna-gamespark.com/ Не упустите шанс сразиться за призы!

Какие преимущества делает Play Fortuna Casino особенным выбором?

Невероятный выбор развлечений от известных провайдеров.

Выгодные акции для каждого пользователя.

Молниеносные выводы в любое время суток.

Удобный интерфейс с эргономичным управлением с любого гаджета.

Круглосуточная поддержка, помочь с любыми проблемами мгновенно.

Регистрируйтесь в Play Fortuna Casino и получайте удовольствие на новом уровне!

Comme son nom l’indique, ce jeu de casino populaire vous emmène dans le sud-ouest américain.

hello there and thank you for your info – I’ve certainly picked up something new from right here.

I did however expertise some technical points using this web site, since I experienced to reload the site

many times previous to I could get it to load properly.

I had been wondering if your hosting is OK?

Not that I’m complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and could

damage your high-quality score if ads and marketing with Adwords.

Well I’m adding this RSS to my email and can look out for a lot more of your respective intriguing content.

Ensure that you update this again very soon.

Hello there, I discovered your web site by way of Google even as searching for a comparable matter, your

site got here up, it seems to be great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hi there, just turned into alert to your blog via Google, and found that it is really informative.

I’m going to watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate in case

you proceed this in future. Many other folks shall be benefited from your

writing. Cheers!

You actually stated that adequately!

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Seldom do I encounter a blog

that’s both educative and interesting, and without a doubt, you have hit the nail on the head.

The problem is something not enough men and

women are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy I stumbled across this in my hunt for something regarding this.

What’s up, I read your blog regularly. Your story-telling style is awesome,

keep doing what you’re doing!

I will immediately take hold of your rss feed as I can not in finding your email subscription link or newsletter service.

Do you’ve any? Kindly let me recognize so that I could subscribe.

Thanks.

We stumbled over here by a different page and thought I might as well check things out.

I like what I see so now i am following you.

Look forward to finding out about your web page again.

my page :: visit our website

Right here is the perfect website for everyone who hopes to understand

this topic. You understand so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I personally would want to…HaHa).

You certainly put a fresh spin on a subject that’s been discussed for ages.

Great stuff, just wonderful! https://menbehealth.wordpress.com/

This design is incredible! You definitely know how to keep a reader entertained.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved

to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job.

I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it.

Too cool!

Very good article. I definitely love this website.

Keep writing!

Hi there, I desire to subscribe for this web site to take newest updates, so where

can i do it please assist.

you’re truly a excellent webmaster. The web site loading pace is incredible.

It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick.

Also, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a magnificent job in this matter!

Very nice article, exactly what I needed.

No matter if some one searches for his necessary thing, so he/she desires to be

available that in detail, so that thing is maintained over here.

Great article.

I was suggested this blog by my cousin.

I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my problem.

You’re incredible! Thanks!

I wouldn t hear nothing After you Understand

Incredible! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a

completely different topic but it has pretty much

the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Ищете лучшее место для азартных игр? Тогда Play Fortuna – прекрасное решение для настоящих игроков! Эта платформа предлагает огромному выбору игровых автоматов, щедрые бонусы и моментальные выплаты. https://xplayfortuna-jackpotarena.com/ – игровая площадка, которая вам понравится!

Что ждет вас в Play Fortuna?

Крупнейшая коллекция слотов от топовых разработчиков.

Щедрые бонусы для постоянных игроков.

Мгновенные выплаты без задержек.

Адаптивный сайт, обеспечивающая комфортную игру.

Дружелюбная помощь клиентам, решающая любые проблемы 24/7.

Попробуйте свои силы в играх Play Fortuna уже сегодня!

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for info about this subject for a

while and yours is the greatest I’ve found out so far.

But, what in regards to the bottom line?

Are you sure in regards to the source?

Hello, i feel that i saw you visited my site thus i came to go back the desire?.I am trying to find issues to

enhance my web site!I guess its adequate to make use of some of your concepts!!

Les amateurs de jeux en direct apprécieront particulièrement la fluidité des flux vidéo et l’ambiance immersive des tables de jeu.

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your web site offered us with valuable information to work on. You’ve

done an impressive job and our entire community will be grateful to you.

Great information. Lucky me I ran across your site by chance (stumbleupon).

I have bookmarked it for later!

What’s upp to all, the contents existing at his website are in act remarkable for people experience, well, keep up the goold work fellows. https://Www.Waste-ndc.pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/

Hello there, You have done a great job. I’ll certainly digg

it and personally recommend to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.

Have you ever considered creating an e-book or guest authoring on other blogs?

I have a blog centered on the same subjects

you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my subscribers

would enjoy your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel

free to shoot me an email.

That is a very good tip particularly to those new to the blogosphere.

Simple but very accurate info… Appreciate your sharing this one.

A must read post!

iird2k

sprunki

I pay a quick visit everyday a few web pages

and information sites to read posts, except this website

offers feature based posts.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I

find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and help others like you aided me.

can you get generic sildalist no prescription can i purchase sildalist prices get generic sildalist without rx

where to get generic sildalist price sildalist drug cost cost sildalist without rx

can i order sildalist for sale

can i purchase generic sildalist without insurance cost of generic sildalist without a prescription can i order sildalist for sale

how to get generic sildalist online can you buy sildalist online how can i get cheap sildalist for sale

сэндвич труба для дымохода

北库历史网 北库历史网

环球理财 hqlc.com

北库历史网 北库历史网

Drugs information for patients. What side effects?

where to buy generic chlorpromazine prices

All information about pills. Read here.

ставки кыргызстан [url=http://bbcc.com.kg/]http://bbcc.com.kg/[/url] .

where to get cheap allopurinol for sale can i order cheap allopurinol online where buy cheap allopurinol for sale

can i order generic allopurinol without rx where can i get cheap allopurinol tablets where can i get generic allopurinol prices

can i get generic allopurinol without prescription

how can i get allopurinol without rx where buy cheap allopurinol online can i order allopurinol without prescription

where can i buy cheap allopurinol price can i get cheap allopurinol without insurance cost allopurinol no prescription

https://uberant.com/article/2000359-unraveling-the-allure-of-gambling-at-spinstralia-casino-a-psychological-odyssey/

Are you a sports enthusiast looking to elevate your betting experience? Look no further than BetWinner, a platform that offers a seamless and thrilling way to engage with your favorite sports tournaments https://tuiteres.es/blogs/22441/BetWinner-Promo-Code-for-Monthly-Player-Rewards-Unlock-Exclusive-Benefits

1xBet – одна из ведущих компаний в сфере ставок, которая предлагает игрокам широкий выбор видов спорта и разнообразные ставки. Одним из преимуществ игры в 1xBet являются бонусные предложения, которые помогут вам увеличить свои шансы на успех и получить дополнительные выгоды https://domel.ru/pags/inc/1xbit_promokod_pri_registracii.html

emma stone nude

Are you a sports enthusiast looking to elevate your betting experience? Look no further than BetWinner, a platform that offers a seamless and thrilling way to engage with your favorite sports tournaments https://znajomix.pl/read-blog/1045

1xBet – одна из ведущих компаний в сфере ставок, которая предлагает игрокам широкий выбор видов спорта и разнообразные ставки. Одним из преимуществ игры в 1xBet являются бонусные предложения, которые помогут вам увеличить свои шансы на успех и получить дополнительные выгоды https://gazetablic.com/new/?melbet_promo_code_free_welcome_bonus.html

jessica chastain nude

mainstream sex scenes

celeb nude

Нужен опытный мануальный терапевт Ивантеевка? Помогаю при остеохондрозе, грыжах, искривлениях позвоночника и болях в суставах. Безопасные техники, профессиональный подход, запись на прием!

частный сео оптимизатор https://seo-base.ru

mostbet войти [url=www.gtrtt.com.kg]www.gtrtt.com.kg[/url] .

what is cleocin pediatric antibiotic cleocin effects side cleocin costs

cleocin antibiotics side effects cleocin for 6 year old cleocin t how supplied

how to get cleocin pill

manufacturer of cleocin cleocin gel for acne where to get cleocin pill

cleocin 300 mg prices where to buy Cleocin cream cleocin while pregnant

Свежие промокоды казино https://www.cbtrends.com/captcha/pages/1xbet_promo_code_for_registration___sign_up_bonus_india.html бонусы, фриспины и эксклюзивные акции от топовых платформ! Найдите лучшие предложения, активируйте код и выигрывайте больше.

where buy motilium pill

order avodart without dr prescription buy generic avodart pills where buy avodart pills

can you get cheap avodart pill where can i get avodart without a prescription can i order avodart for sale

can i buy avodart without prescription

cost of avodart how to buy cheap avodart without prescription cost of cheap avodart prices

where can i get avodart without a prescription avodart 60 mg daily avodart cheapest price

can i buy generic motilium online